Genetic engineering is the process by which scientists change the DNA of living things. Those living things will then have different characteristics. For example, tomatoes being altered to taste sweeter or goats being made to produce spider silk.

In recent years, technology has allowed scientists to modify the DNA of people to treat diseases caused by genetic mutations. However, the modification of human DNA presents the dilemma of inequality, as expensive gene editing treatments are only affordable to a select audience.

Genetic Engineering and Medicine: Gene Therapy

Before the 2000s, gene editing was limited by the tools available, so it could only be implemented on bacteria and grocery fruits. Since then, the invention of CRISPR/Cas9 has allowed scientists the possibility of gene editing on people.

Medical ethics professor at the University of Podstam in Germany, Robert Ransich, and researcher Mary Almeida have expounded upon the consequences of gene editing in a “Nature” article.

“Compared to counterpart genome technologies (e.g., ZFNs and TALENs), CRISPR/Cas9 is considered by many a revolutionary tool due to its efficiency and reduced cost. More specifically, CRISPR/Cas9 seems to provide the possibility of a more targeted and effective intervention in the genome involving the insertion, deletion, or replacement of genetic material,” said Ransich and Almeida.

With its newfound precision, treatments known as gene therapies are more common in the medical field. These treatments are limited to very specific diseases—single gene disorders. These diseases are known to be caused by a certain gene, allowing for scientists to easily modify the gene and treat disease. Currently, there are over 30 gene therapies approved by the FDA to treat cancer, sickle cell anemia, hemophilia and other single-gene disorders.

The Dilemma of Advancement

As scientists gain an understanding about the human genome (the collection of all the genes in a person), gene editing may have the potential to advance wealth inequality.

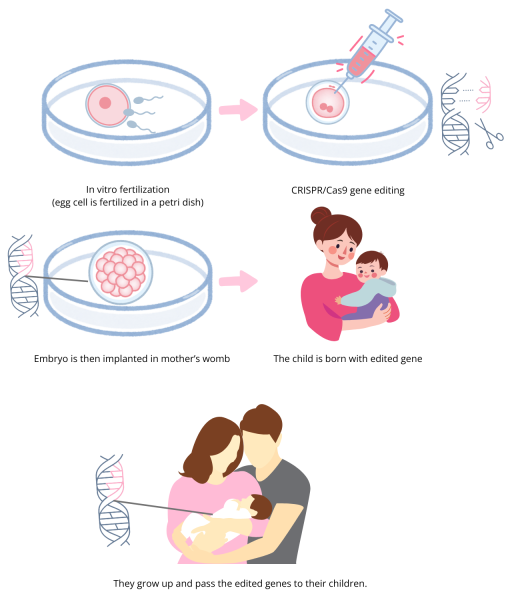

Heritable genome editing is when DNA is modified in reproductive cells; thus, the children, grandchildren and the rest of the generations will be affected by the editing. This has the potential to create families whose generational wealth also comes with a medical advantage.

“Another concern is that if heritable genome editing were to become prevalent among those who are wealthier or better insured, it could change the prevalence of avoidable diseases between advantaged and disadvantaged populations,” said the National Academies Press, the press department under the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM).

Affluent populations would then be advanced both in terms of wealth and health, at least for the diseases that can be prevented by gene editing treatments. That is, families who are already advantaged with money will be less susceptible to single-cell diseases, as will their children, their grandchildren and so on. Meanwhile, poorer populations will still be struggling to catch up, both economically and medically.

However, Christopher Soch, a math teacher at Huntington Beach High School (HBHS) with a Bachelor’s in Philosophy from the University of California Los Angeles, claims that it is better to start with the wealthy and spread treatments from there.

“Think about vaccines or access to food. We don’t stop the release of vaccines because we know that some countries won’t have them. We would rather increase access to better healthcare, even if it starts with a few, select individuals, and go from there, rather than decrease access to healthcare,” said Soch.

Present Concerns

Currently, geneticists don’t know enough about human DNA to develop heritable gene editing. Existing treatments are limited to rare diseases with known causes—none of which are heritable.

Many are familiar with the dystopian idea of scientists “enhancing” the human genome—for example, controlling eye color, intelligence or strength. This would be a surefire way to increase inequality, as groups with access to treatments will gain advantages in more than health alone. Despite these concerns, the human genome is far too complex for scientists to pinpoint exactly how to enhance specific physical traits or decrease susceptibilities to most diseases. Thus, it is unlikely for primacy in edited characteristics to be a concern in the near-future.

“Similar to many diseases, in which different genetic and other factors are involved, many of the desirable traits to be targeted by any enhancement will most likely be the result of a combination of several different genes influenced by environment and context,” said Ransich.

Soch claims that the desire for advancement—to increase the human lifespan, to prevent disease, and to thrive as a civilization—supersedes concerns of inequality. That is, the rush for advancement is a greater priority for Americans.

“There is an incessant pace to change and innovate rather than strip back and slow down, enjoy friends, family, life. If we don’t judge it for a second and just think of it as this progress-oriented change for some concept of success, some aspect of dominating, then I think that all of this is ‘justified’ and the inequality is secondary. If that’s our cultural kind of outlet, then it never was about equality,” said Soch.

The pace of advancement in heritable genome editing has been slowed down by federal policies. In 2019, the National Institute of Health proposed a moratorium (a temporary ban) on permitting gene-editing human embryos or any related clinical trials.

In 2020, the House of Representatives passed a bill preventing the Food and Drug Administration from approving any germline editing clinical trials. This bans modifications of human babies and any other modifications which could be passed from generation to generation. However, gene therapy treatments are still being developed and tested to treat more diseases and conditions.