Across the country, student journalists are often faced with invisible lines and unspoken limitations that dictate what they can and cannot say. “Boundaries usually exist for good reason, but journalism is never about boundaries,” said Michael Simmons, advisor of Huntington Beach High School’s (HBHS) news magazine show Campus Update. His words reflect a challenge that extends far beyond just one classroom or institution.

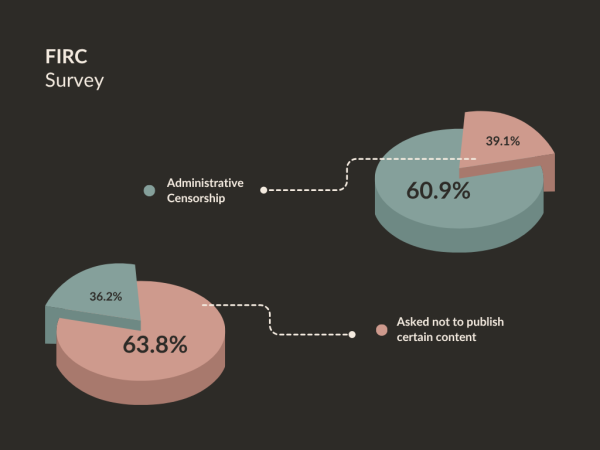

In fact, a survey of college newspaper editors by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) found that 63.8 % of editors experienced at least one instance of administrative censorship the previous year. Another 60.9 % of editors reported being asked not to publish certain content. These figures show how widespread censorship influences which stories see the light of day. Fortunately, California stands apart. The state is one of the few that protects student journalists through laws banning prior review and prior restraint, meaning school officials cannot censor content before it is published. It’s a freedom many student reporters across the country do not have, and one that should not be taken for granted.

From student journalists deciding what is “too controversial” for a school publication, to professional reporters whose stories are edited to fit a particular narrative, censorship continues to dictate which stories get published and which remain in the drafts. As each generation navigates the immense responsibility of reporting the truth, one question remains: when does managing the message turn into muting the messenger?

Student journalists often face limits that influence what they publish and how they perceive their role in the classroom. These boundaries might be set in place by teachers, advisors or administrators reviewing content. On the other hand, the student may fear backlash from their piece or be concerned for their safety. A national survey of high school journalism programs from the Student Press Law Center (SPLC) found that 32% of student journalists and 39% of advisers said school officials told them not to publish or air certain content. While the survey dates back to 2014, the lack of recent national data regarding this issue underscores how censorship in student media remains under-analyzed. From local politics to sensitive social topics, these restrictions continue to shape what stories students feel comfortable covering and which ones never make it to print.

As Allison Vo, HBHS Yearbook Writing Editor, said, “If we aren’t able to talk about those hard topics, people can lose their voice and we could suppress potential awareness.”

Losing that voice affects more than confidence, it reshapes how students view journalism itself. Many begin self-censoring, avoiding meaningful stories and questioning whether their efforts really matter.

“The Yearbook is a time capsule of not just our time in high school, but what was going on that year. I want us to be able to look back on how we’ve changed in policies, as a community and as people,” said Vo.

Her words highlight how student journalism preserves identity and history, if allowed.

Audrey Chau, a producer of “Baron Broadcast News” (BBN), a news publication at Fountain Valley High School, said, “I hope schools provide an open and diverse platform for students to express their feelings and ideas.”

Together, these perspectives challenge the notion that student media must stay within safe, noncontroversial lines.

Regardless, those lines are not easy to navigate. Even dedicated student journalists must learn to balance risk and responsibility.

Simmons said, “I would advocate for being balanced, mature, and try to explore the topic from all sides, making sure that differing perspectives are addressed.” He suggests students ask: Will this bring clarity or just provoke conflict?

That balance of courage and care is shared by many young journalists.

HBHS Slick Journalism alumnus, August Berrios, said, “You shouldn’t fear covering these topics, but you have to be careful with the way you present your story to make sure it curates a positive impact rather than a negative one.”

Controversy isn’t off-limits, but the storytelling must be thoughtful.

Professional journalism carries similar challenges. Owner of HB Living Magazine, Scott Rogers, said, “Be honest about what you write, check your facts and do your best to leave your opinions out… I think people on all sides are more likely to attempt to censor speech they don’t agree with today.”

Truth can be caught between public pressure and editorial control even outside school walls.

Despite these pressures, many student journalists persist. Kyle Vu of BBN said, “An important process in keeping our program student-led is balancing school boundaries and student voices.”

For Vu and others, journalism isn’t about avoiding complex stories; it’s about how to tell them responsibly and courageously.

Around the country, students face legal challenges as well. The Supreme Court’s Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier (1988) decision allows administrators to censor school-sponsored media under certain circumstances, according to SPLC. In response, 18 states, including California, have passed New Voices laws, which protect student press freedoms beyond Hazelwood’s framework. These laws prevent censorship unless a story is libelous, obscene or disruptive, restoring more freedom to student expression.

Even at the global level, press freedom faces pressure. The United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) identifies disinformation, censorship and violence as the top threats to journalists worldwide. The challenges student journalists face serve as a microcosm of struggles in the broader world of journalism.

Censorship will continue to evolve, but so will those who challenge it. Each generation faces the same decision: stay silent or speak up. For now, a student can be behind a school camera, but one day they could be in a national newsroom. As Simmons said, “Push boundaries if you want, but really, just pursue and value truth. In the end, truth is our only defense against ourselves.”