The Fallen Majesty of Britpop

How the music that shaped the biggest rock band of our generation fell on deaf ears in the United States.

October 25, 2022

A nineteen-year-old Alex Turner, his neighbors Matt Helders and Jamie Cook and their secondary school friend Andy Nicholson would soon change the rock landscape forever in 2006. That year, the Arctic Monkeys released their debut album Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not—an energetic tour-de-force of wordplay. With acts such as The Strokes, Franz Ferdinand, and the Libertines, rock had found its newest incarnation; the grimy, stripped-down, melodic cool of garage-rock revival and its fuzz-box distortion. The Monkey’s monumental arrival with their duo of number-one singles “I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor” and “When the Sun Goes Down” was not only a sign of times but another addition to the halls of era-defining British musicians.

By 2006, the UK music scene was in need of a strong, identifiable movement. The Spice Girls were on break, and the “Cool Britannia” movement, a term used to describe the revitalized sense of national identity felt by Brits after economic growth in the 1990s, became a mockery of itself. The Arctic Monkeys were the head of a new movement that got the nation excited again. However, this period of dirty guitar tones and catchy alternative music was not new to Britain.

As one of the fallen pillars of “Cool Britannia,” Britpop did the same thing in the decade before, a front as integral to the UK as punk was in the 70s. Unlike the Arctic Monkeys, their Britpop influences never made it big across the Atlantic due to not having what the Monkeys possessed: good timing.

The Beginning: “Modern Life is Rubbish”

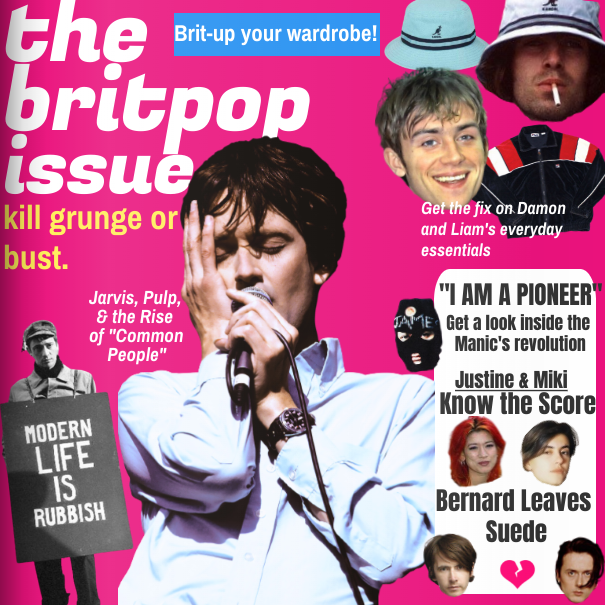

Britpop, like any genre, is difficult to define. However, it is best remembered as the period between 1992-1997 in which alt-rock depicting British life dominated the UK charts. There were artists at the forefront of the movement who didn’t subscribe to certain aspects associated with it; bands such as Suede, Manic Street Preachers, and Placebo utilized femininity to counter the “laddish” image popularized by Noel and Liam Gallagher of the music group Oasis. Ensuring that the image of an underground, youth counterculture remained intact long after musicians found themselves displayed across magazines and the evening news.

According to Susan Higgins, a hairdresser who grew up in the UK, her memories of the genre came much earlier. “Other than hearing ‘I Wanna Hold Your Hand’ by The Beatles on the radio when I was small, I mean, maybe that’s going way back. A really good memory was listening to The Smiths’ and I’m pretty sure I was in 5th grade when ‘How Soon Is Now?’ was on the radio,” said Higgins.

As Toni Collette in the music film, Velvet Goldmine once said, “What’s true about music is true about life.”

The truth is that ideas are a culmination of deep personal influences and outside circumstances. With the release of two seminal singles in 1992—Blur’s ‘Popscene’ and Suede’s ‘The Drowners’—the floodgates of young artists looking back onto British music history, and transforming it, were opened.

‘Popscene’ was a catalyst for action. With lead singer Damon Albarn beckoning listeners to “come out tonight,” the ‘Modern Life is Rubbish’ album served as a wider criticism of capitalism and its “chrome-colored clones.” As the blaring horn section and riotous guitars from Graham Coxon created unstoppable momentum, Albarn’s mock-cockney accent delivers the anthemic well-known phrase “in the absence of a way of life/just repeat this again and again.”

For Suede, “The Drowners” was an introduction to the rhythmic sleaziness that would come to define their first album. Lead singer-songwriter Brett Anderson delivers an ode to finding young love with the wrong people in the wrong places, calling lovers, “real drowners”. The London group tapped into the sexual ambiguity of 70s pioneers such as Roxy Music and T.Rex, with Anderson delivering the line “we kiss in his room to a popular tune” surrounded by glam embellishments.

Suede rose to prominence directly after their first single and would be dubbed “The Best New Band in Britain” by Melody Maker. Their debut album, Suede, would be the best-selling British album in over a decade—a record that would be broken by Oasis’ Definitely Maybe in 1994. Only the Arctic Monkeys were able to surpass both bands, breaking the record in 2006.

“Do You Believe in Love There?”

The political atmosphere was largely influential on the music writers were composing. Dating back to the Industrial Revolution, the United Kingdom has been divided into the more urbanized South and industrialized mining towns of the North. Following the 1984-1985 Miners Strike—in which miners fought against the conservative Thatcher government and its systematic closure of coal mines—the difference between the two regions became more apparent.

Given its natural resources and history as a mining region, the North never received the infrastructure to create cities like the South. The South, like London, holds one-third of the country’s population. That being said, the Southern region is responsible for 45% of the economy and 42% of the national wealth.

As Susan Higgins gave her recollection of Britpop, the intersection of music and politics was undeniable. Higgins said, “In England, once you’re low class you’re kind of just stuck there forever.”

Higgins mentioned that her nieces were able to go to school in London. While getting their education in an affluent area, Higgins said that her nieces were exposed to the sentiment that, “[They could] be anything [they] want[ed] to be, just don’t be common.”

When Suede asked the question “Oh, do you believe in love there?” in “The Drowners”, it refers to more than navigating a complicated love life. Suede is referring to the feeling of growing up during a time of economic turmoil, in a desolate town offering no escape.

The muddiness of their sound and identity comes from the shadows of impoverished cities. Or as Oscar Wilde put it, “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

When music group Pulp burst onto the scene in 1995, they not only created an immaculately arranged set of songs but a manifesto stating that “common” people—the people they could relate to—were just like anyone else.

In the opening song “Mis-shapes”, frontman Jarvis Cocker sets the stage for intellectual revolution, “we won’t use guns, we won’t use bombs/we’ll use the one thing we’ve got more of/that’s our minds.” Backed by lyrics on being consistently dehumanized due to socioeconomic status, Pulp expressed emotions that the systematic failure of the class system could not suppress.

Mainstream Success: “Live Forever”

After the success of Suede, the amount of attention put on the British indie scene increased. By 1995, landmark albums like Blur’s Parklife, Elastica’s self-titled, and Pulp’s Different Class—all touching on the confines of 90s gender roles—hit #1 on the charts.

The previous year, Britpop gained its most polarizing and internationally successful act: Oasis. Best known in the US for “Wonderwall”, a song still played on a daily basis across alternative stations, their reputation of combative arrogance precedes them.

No matter the amount of controversy Noel (elder brother, guitarist, songwriter, and Liam (singer, attitude, and quintessential younger brother) Gallagher could generate, something about their music spoke to the masses. Within months, the brothers had an interview recording that made it to #52 on the singles chart. Their knack for creating particularly explosive insults was first displayed to the nation.

The argument topic in question regarded the disastrous start of their first European tour; in which every member of Oasis—except Noel—was arrested and deported after a drunken brawl on a Dutch yacht. By the two-minute mark, the tension created by differing opinions on the press fallout was palpable. Noel wasn’t exactly proud of the event. Liam wore public notoriety like a badge of honor, calling the event “[redacted] boss.”

Although, that was not the only feud taking place.

Blur had the media and charts captivated. Parklife was huge. Damon Albarn and Justine Frischmann of Elastica had paired up to form Britpop’s very own power couple. This power was exemplified when Blur took home all four Brit Awards they were nominated for in 1995; taking all but one award Best British Breakthrough Act from Oasis. The 1995 Brit Awards was monumental in showcasing that the youth-led genre was critically and monetarily valuable. And for the first time in years, indie bands were winning awards.

Following a celebratory photoshoot at the awards in which Blur guitarist Graham Coxon, clearly intoxicated, was photographed kissing the cheek of Liam Gallagher, the resentment between the acts could be felt through the magazine cover alone. The “Battle of Britpop”, as we know it, had begun.

When learning about the legendary feud, it is integral to understand how class shaped the way each band was perceived.

Oasis came from a working-class background in the Northern city of Manchester. The Gallaghers were raised primarily by their mother, Peggy. The family was not at the point where vocal lessons, let alone pursuing the arts, were something they could afford. And yet, they persisted.

In the track “Supersonic” on their debut album Definitely, Maybe, Liam snarls into the mic, “You could have it all but how much do you want it?” Any other band would take the lyric as a playful gesture, but the magic of Oasis lies in Gallagher’s uncanny ability to create a consensus with the audience that he means every word he says. And at that moment, it is made clear that the lyrics are a lifeline of the band too.

On the topic of Definitely Maybe, Higgins confided that “I love that album so much because it has all the ups and downs the perfect album needs to have, y’know? And that [it’s] good listening to it in a crowd, but it can save me on my own as well.”

She said, “[Definitely Maybe] helped encourage me [to see] that my future was worth waiting for.”

Blur’s origins take place on the other side of the poverty line: middle-class life in the South of England. Since the media plays by stereotypes, this meant that the members of Blur were perceived as better off and more educated than their Northern counterparts. When faced with class stereotypes, Blur’s case was not helped by the fact that the band’s full lineup came to fruition at Goldsmiths College in London.

“Oasis was seen as being cooler [due to being from the North] because Blur never worked for anything. Because Blur [was] always [seen as] given stuff on a silver spoon.” Higgins said.

The single off Oasis’ now-classic What’s the Story Morning Glory?, “Roll With It”, was slated for an August 14th release date. Given the band’s large following, the song was engineered to hit #1. Meaning that the group would also get to bask in their own glory during the prime-time showing of Top of the Pops. Getting wind of this, Blur’s label, Food Records, moved the release of their new single “Country House” to the same day. The battle for that #1 spot on the charts had been set.

If the Brit Awards were considered an appetizer, the press received their meal in mid-August. The songs released gave sight to artists not fueled by creativity: but by competition. “Roll With It” was overblown, even for Oasis. And “Country House” saw Blur’s pompous caricatures of the upper class lose their irony, turning into an anthem for the wealthy instead. Despite the creative deficiencies, “Country House” and “Roll With It” sold 270,000 and 220,000 copies in their first week respectively.

Blur won out in the end. Edged out by 50,000, Oasis had to watch Blur bassist, Alex James, perform on Top of the Pops mockingly donning an Oasis shirt.

The Battle of Britpop was a battle of the superficial. Looks, sales, and money were placed above the art both bands had previously made. Sales over authenticity; entertainment over people.

Burnout: “What Exactly Do You Do For an Encore?”

Britpop’s demise can best be explained by Pulp’s “This Is Hardcore” music video. A seedy brass line leads viewers into a pristine movie set. Actors displayed in numerous stages of filming contrast the washed-up sonic landscape. Young men and women are showcased in their prime as Jarvis Cocker groans, “you got to take these dreams and make them whole/this is hardcore/there is no way back for you.” The image Cocker paints is dreary. Young hopefuls pay the price of their ambition for the rest of their lives, stuck in the machine of tabloids.

The song reaches its crescendo at the bridge. Removed from the sound stages of manufactured bliss, Cocker walks down a pink hallway lined with girls in Vaudeville getups and tacky chandeliers. He brushes past their handheld fans, and stares down the audience as he states, “this is the eye of the storm/it’s what men in stained raincoats pay for.” Pulp places the fault of their burnout on the press and their voyeuristic role in watching fame destroy the people who gained it too early. An element of perversion is conveyed—a further indictment of the predatory British media.

Pulp’s verdict was exactly right. The music industry did not, and does not, create an environment where musicians are seen as people. Sobriety is sidestepped for productivity. And humanity is replaced by glossy, processed images of satisfaction.

According to Honors English and Environmental Literature teacher Mrs. Harshman, “[Fame is] such a hard thing, because for so long, especially with punk music, it was looked down upon to sell out and become famous. But now, in this world, it’s totally accepted because we realized that’s how you make a living and that’s how you can survive selling your art. And that’s wonderful. But that is [a] double-edged sword, once you become so famous then there is literally no privacy. And there is no going back.”

“This Is Hardcore” feels like waking up after a party and turning on the lights. And truly seeing yourself for the first time, finding that you don’t exactly like the person who’s staring back.

As the video comes to a close, the camera pans out from the confines of the sterile sets. The cameras, lights, and microphones are exposed—the actors stop completely. And the horror of being alone in pursuit of a career in the public eye is finally realized.

After being used for years and years, Pulp worked with what was left. The song trudges on, its jaunty melody takes on the syncopation of a limp—all while begging the question, “What exactly do you do for an encore?”

Victim of Grunge

The toll of fame was not the only thing killing Britpop’s momentum. Oasis aside, the genre was plagued by an inability to gain popularity in America. This is heavily due to the fact that the States were preoccupied with their own revolution: grunge.

Britpop and grunge were different sides of the same coin. Both criticized the social institutions in place—however their way of doing so differed entirely. If Britpop can be depicted as the bright-eyed, macho-posturing dandy sticking his nose up at the gloominess of the ‘91 US music scene, grunge can be considered the apathetic, sludge-toned, glassy-eyed counterpart. The “look” of both scenes contrasted so much that they were deemed incompatible.

After moving to America in her teens, Higgins began to realize the musical differences when visiting the UK in 1990. She said, “There was [so much] different music on the radio in England from what there was [in the United States].”

Higgins recalled, “[There were] Nirvana and Pearl Jam [in the US]. But what was coming out of England was gentler, it was different.”

Just as Britpop permeated most corners of British pop culture, grunge was inescapable in the United States.

Mrs. Harshman grew up in the US when grunge was at its peak. “Even growing up, thinking about generational differences, I grew up in a small town but we had like one record store where you had to order and preorder [music] months in advance. And just learning about music was so much more difficult being so secluded. And I’m sure at that time it was so much harder for British bands,” she said.

Music accessibility has been a pathway for understanding between scenes divided by geography and ideals. The forerunners of Britpop were not afforded the same luxury. Coming out of the 90s and into the 2000s, the Arctic Monkeys found themselves in an age where “breaking” the US was more tangible than ever.

Looking Forward With Arctic Monkeys and “The Car”

The Arctic Monkeys’ newest album The Car is scheduled for release on October 21. They have effectively dominated the globe, becoming the biggest rock group of their generation.

When asked about how she got into the Arctic Monkeys, HBHS junior Charli Nguyen said, “It was because of TikTok. If I think about it, I think I heard [the Arctic Monkeys] on the radio not knowing who they were. And then [Arctic Monkeys] started popping up on my TikTok more and more, and then that’s what kind of started getting me into their music.”

After gaining exposure to the band, Nguyen said, “From there it’s just like [my] obsession grew.”

They’ve been admired for their aesthetics, most famously the black-and-white rockabilly of 2013’s AM. With their single “Body Paint”, the group takes on another strong style direction. Its orchestrations evoking the color-washed palette of the 70s.

The Arctic Monkey’s have come far from their hometown of Sheffield. They transcended the scene they came from and polished their sound as their artistry grew. As the guitar ebbs and flows, Turner’s confidence exceeds his 19-year-old facade. One can’t help but compare the impassioned delivery to Liam Gallagher’s on “Rock N’ Roll Star,” an opening track that serves as a thesis statement of the band’s future stardom.

It becomes apparent that the Arctic Monkeys were always meant to take their place in music history. The attitude displayed by the band early on gives the impression that their rise was cosmically aligned.

After an evening of reflecting upon the music she grew up on, Susan Higgins turned her focus on the future. Life in the United Kingdom has drastically changed in the past few months. Along with the nation, and the world as a whole, still reeling from COVID-19, the UK has gone through three prime ministers and lost their longest serving head of state in less than three months.

Higgins said that she believes music will be the remedy to the challenges that come with social and economic change. “[The creative cycle] should repeat over and over because the human condition is not getting much better. If anything, we are reaching out for more [music] than ever. We want to make sense of life and we want to ‘stick it to the man’ and all those things…We need that comfort and help more than ever.”