Japanese Internment Camps: The Story of One Resilient Woman

April 18, 2023

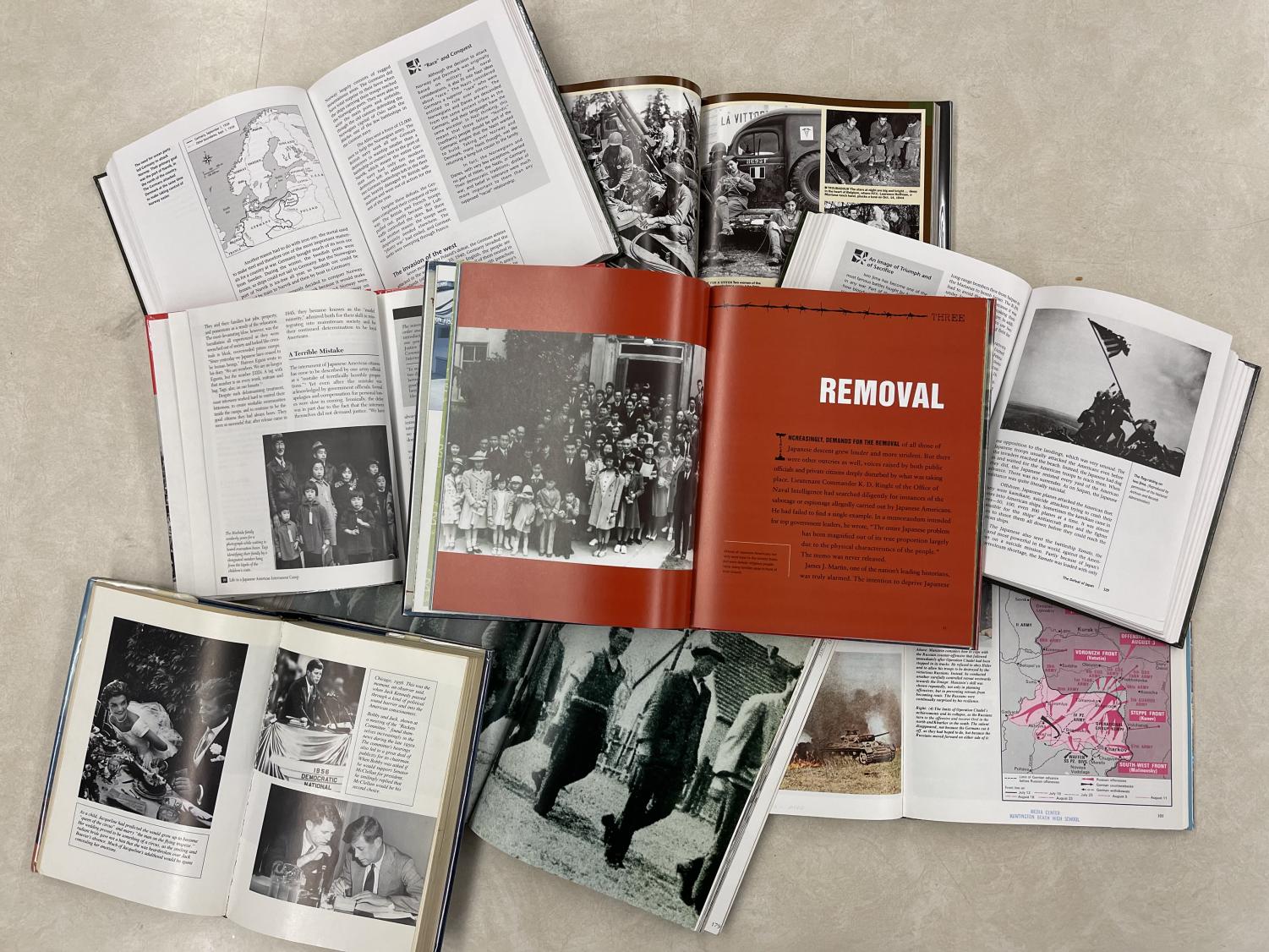

During World War II, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Two months after that, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066—creating the infamous Japanese internment camps. Exclusively for Slick Magazine, an anonymous source who was in the camps as a little girl, tells her story, depicting what it was like growing up in the camps and life after her release.

When the executive order was issued by President Roosevelt, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt issued a curfew for Japanese Americans. Then, in the span of 6 months, 122,000 Japanese-Americans were forced to move to an assembly center and then to relocation centers, better known as internment camps.

The internment camps were not in the best conditions. Most of the time the people lived in a room with a cot and stoves that only used coal. All of the residents used communal bathrooms and laundry machines. The camps were surrounded by barbed wire and had guards that were on the other side, all armed with guns.

Our anonymous source was put into the camps as a little girl. She was put into the camps with her mother, father, and grandparents, along with her siblings.

She began talking about her memories of her father and grandfather being taken before the rest of her family. At the time, they had not received U.S. citizenship and were classified as Japanese immigrants. The two moved from camp to camp about every week, and after three weeks, the rest of her family—including herself—were taken to the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona. She recounted that “Poston was one of the larger camps. There were three sections and over 17,000 people among the three camps.”

She would often speak with her mom about the camps. She said, “I asked my mom once about how she felt about being uprooted…The attitude was [that] the government tells you, you have to go, you obey, it’s the law.”

After they were told to move, they went to different places. Some were sent to California and a few to Arizona. This all happened in the span of two weeks.

She also remembers that life kept moving on, pools and churches were built in the camps and the children played and went to school. She also talked about going through preschool and kindergarten as a girl living there, saying, “people built. They took supplies from whatever the government had sitting around.”

After she and her family were released, they refused to discuss the topic. She thinks her family not talking about the situation helped the healing process. “We are a generation of people [who] don’t know a whole lot just because we just didn’t talk about things,” she said.

After the release of their family, neighbors, and friends helped them sell crops they grew because most companies would not take the harvest from Japanese families willingly. After selling their produce to others, her household would take them to market and return with the profits so they could make a living without facing racism from the community.

Her mother also didn’t want her and her brothers to start school because of the bullying they may face. The time period when they were released from the internment camps was right at the end of the school year, and their mother felt it wasn’t wise to put them in so close to the end of the year.

She briefly mentioned meeting people in college who had a different experience than her with the camps. “I have since met people who lived in different places who had very different experiences and my own peers who were very bitter about their own experiences, but I guess I have my family to thank for not having given us that kind of bias,” she said.

It’s important to note that her story is different from everyone else in the camps and not to assume that her experience is like everyone else’s.

To this day, she remains living a healthy and happy life and does not allow the trauma of her earlier experiences to affect her and the quality of her life now.