Wes Anderson, an American director and writer, is known for his eclectic props, bright coloring, symmetrical frames, and quirky storytelling. Some of his most famous films include the childish story of Boy Scouts and young love in “Moonrise Kingdom” (2012), a European hotel adventure that involves death, prison, and baked goods titled “The Grand Budapest Hotel” (2014), and a standout claymation movie about animals versus farmers—”Fantastic Mr. Fox” (2009).

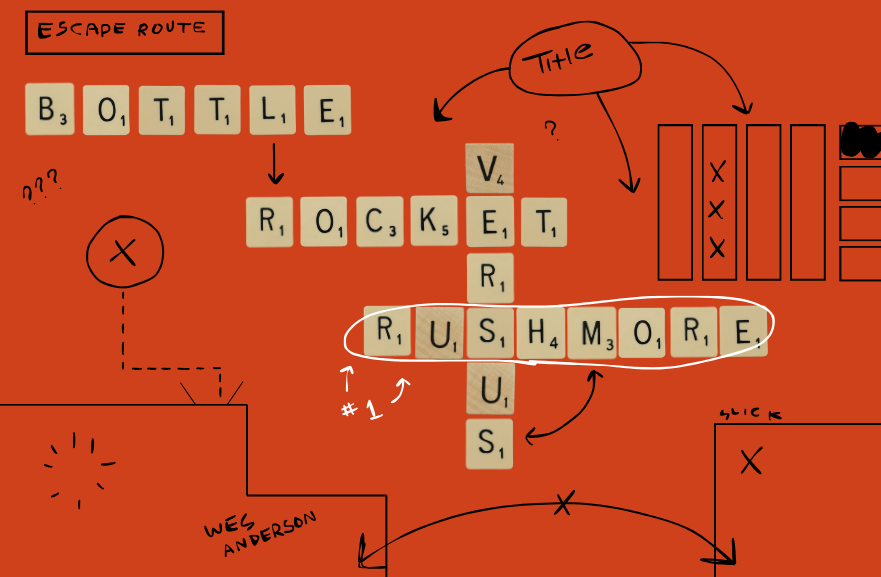

However, some might find it surprising that his debut feature-length film had all the same tell-tale signs of Anderson’s well-known isms (like shots of busy hands, defining character looks, and iconic instrumentals), despite being released in 1996. The film was based on Anderson’s black and white short film of the same title and featured the same main cast: Owen and Luke Wilson, and Robert Musgrave. The plot was a simple comedy-crime heist, but supposedly Anderson thought he could turn it into something bigger—like a 100-minute movie to (bottle) rocket launch his career.

Anderson was dreaming big, despite a low budget, small cast and crew, and a contained plot all shot on 35mm color film. Even within the first five minutes of the movie, you’d immediately recognize all the dead giveaways that this is an Anderson movie. It has uniform shots, standstill cuts of oddly aesthetic buildings, vintage cars, a romantic dream girl, weird character names (Dignun), and an iconic song in the soundtrack (“2,000 Man’‘ by The Rolling Stones).

This movie is the blueprint, visually, for all his forthcoming movies after this. “The Aquatic Life with Steve Zissou” (2004), also featuring O. Wilson, has plain-yet-memorable outfits, peculiar hats, symmetrical ‘freeze frame’ shots, and DEVO on the soundtrack. A newer film in his filmography, “The French Dispatch” (2021) has iconic frames, bursts of color, and recognizable cast members (O. Wilson, again).

It’s undeniable that he has cultivated a certain distinctive image over the years. The people behind his films pay close attention to the details in set design, costuming, props, music, and color grading. The reason people remember the suitcase set in “The Darjeeling Unlimited” or the binoculars in “Moonrise Kingdom” is because they are subliminally made novel. It catches the attention of the viewer because it’s an uncommon thing to see in the modern day, or because it gives a sense of ‘FOMO’ (Fear of Missing Out) because they’re period pieces. Every car in “Bottle Rocket” is vintage and colorful for a reason, you’re not going to see a Dodge Caravan because Anderson doesn’t want you to, he wants you to remember the firetruck red Volkswagen Bus.

After carefully stylizing his first film and developing a distinct style that makes a comeback in “The Royal Tenenbaums” (2001), his second film’s general aesthetic comes as a sort of surprise.

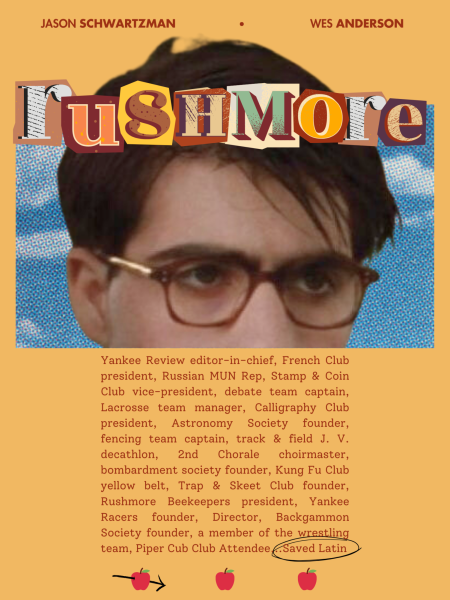

Although Anderson is often regarded for his talent due to his obvious aesthetic that he’s made so recognizable and cultivated a following for, some viewers get lost in the whimsy and lose the plot. Anderson being the visionary he is, has a plethora of beautiful films, and while his image and cinematography style are very pleasant, “Rushmore” proves his movies don’t need all that glitz and glam—or blunt vintage touch—to be amazing.

“Rushmore,” starring now long-time Anderson actor Jason Schwartzman, is about a tryhard academic under scrutiny for his poor grades and constant antics. The film follows Schwartzman’s teenage character, Max Fischer, throughout a surprising and inappropriate love triangle and a hectic, self-written play. Unlike this movie’s predecessor, it is far less colorful and lighthearted. All the serious scenes from “Bottle Rocket” are short or backed with more romps and hijinks—all seriousness in “Rushmore” feels more detrimental for the character, like he might not make it out okay in the end.

The only real indication that this movie is in fact by the same director on a surface level is the memorable still shots, symmetry, and Max Fischer’s red hat. However, this film is probably Anderson’s best work out of his entire filmography. It is so relatable yet simultaneously striking, and every moment feels like an entertaining, well-crafted cut perfectly stitched into a comprehensible movie.

While many Anderson films have gathered a massive following of people trying to replicate their unmistakable look, the films are not simply ornamental. Look beyond the cursory critiques and find the depth.